There is a joke in this, but first I need to set the scene. In Sept 2013 I visited my local bank in Spain, Andalusia. After subjecting my status to some minor inquisitions I departed with a quotation for a mortgage. Yay! Actually, I learnt retrospectively that the quote was not legally binding but nonetheless Our Great Property Hunt was officially underway. Sometime later, my family and I found our dream home and I returned to the bank to refresh the quotation against the agreed sale price. No problemo. Armed with the confidence of an approved budget we set out to fulfill our part of the bargain and source the deposit (forty two percent of the sale price).

This meant selling our family home back in the UK. Given that we lived in a small community with some of the most fantastic people I have ever met, this was definitely the toughest part. But we did it, paid a deposit to the Spanish seller (ten percent of the sale price) and returned to the bank to seal the deal. What happened next was a mysterious series of:

- Computer system failures

- Banking staff absent

- Zero response to communications

- Ambiguous and conflicting messages from .. Madrid

Time passed. We recruited a Spanish lawyer. A great guy, very determined with oodles of experience, but even with this mighty assistance we were still unable to find a resolution. We tried again with another bank. Much the same story, but after forty days we received this email (translated from Spanish).

The appraiser (TINSA) gives me a very low value, 20 percent of the sale price.

I understand that with this value we cannot provide the mortgage.

Thank you and regards

I contacted TINSA directly to try and understand what had happened. Like the banks, there was no response. We kept trying with other banks but it was agonisingly painful as all followed a pattern that I can best describe as a strategy of procrastination.

So what’s the problem here?

Well really there are only two possibilities. Either they don’t like my house or they don’t like me. Despite an increasing sense of paranoia I can’t accept that it is anything to do with me. None of the banks have raised any concerns about my Age, Income, Nationality or any other aspect of my status. The house is the problem. It could be that it is because the house is classified as a Casa Rustica (Country House). Of the 2,823 mortgages granted in Andalusia last month only fourteen percent were Rusticas. The remainder were Urban Dwellings.

Data sourced from the National Statistics Institute (INE).

To put those mortgage approval figures from INE into some context, In April this year, La Vanguardia reported that:

The signing of new mortgages for home purchases fell by 33% last February over the same month of 2013 and has already accumulated 46 months of declines, according to data released today by the National Statistics Institute (INE ).

But nevertheless 408 mortgages were granted to lenders buying Casa Rusticas, so why do the banks decline my business? The other possibility is that the bank doesn’t like my house because it is not owned by them.

Let’s think about that.

On the 9th June 2012, the BBC covered the Spanish bailout.

Spanish banks to get up to 100bn euros in rescue loans.

At the time, Senor de Guindos (Spain’s economic minister) said

We hope that as a result of these injections [of capital] families and companies will have more solvent banks which are able to offer them credit.

So the intervention of Senor de Guindos should have helped me right? Let’s look at some numbers. These are extracted from The Bank Lending Survey, published by the Bank of Spain.

The Bank Lending Survey is an official quarterly survey that has been conducted in coordination by all the euro area national central banks and the European Central Bank (ECB) since January 2003.

From the survey, I became interested in the following question.

Over the past three months, how have your bank’s conditions and terms for approving loans to households for house purchase changed?

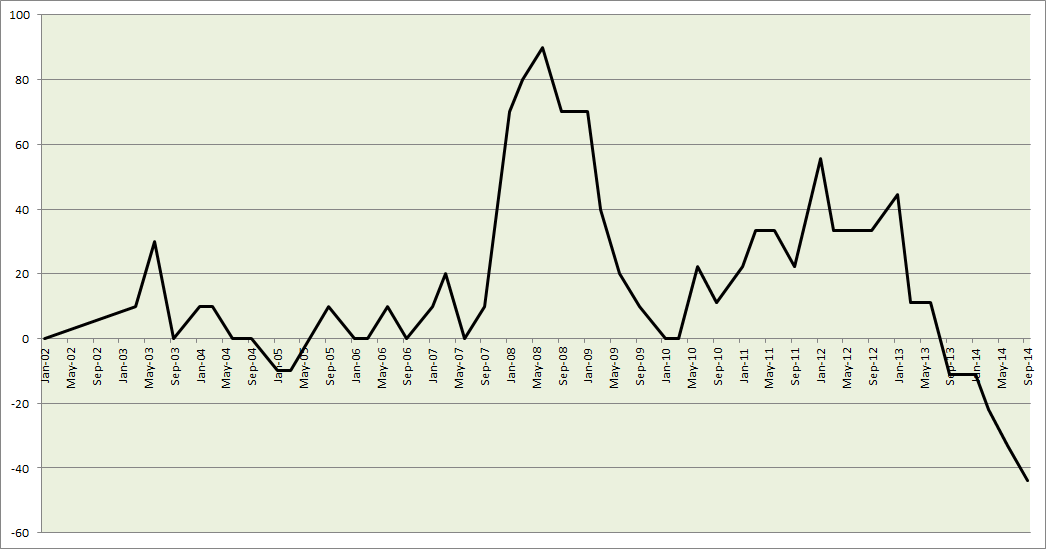

The following chart shows the share of banks reporting that terms and conditions have been tightened, minus the share of banks reporting that they have been eased.

So that’s pretty clear, the banks basically shut-up-shop after they got the bailout. Senor de Guindos’s hopes were not realised and the reason for the lockout is because the banks tightened their T&Cs. But can we go further? Does any of this show that Spanish Banks are actively obstructing mortgage applications in order to promote the sale of their own toxic stock? Well not necessarily. To know that for certain we’d need to know whether the mortgages that were approved were on properties owned by the banks. And to the best of my knowledge, the banks don’t publish figures to show that. Looking more broadly for circumstantial evidence however, The Economist wrote that

With more than 600,000 new homes still unsold, a flood of new properties onto the market would hurt both banks and house prices.

And this Bloomberg article about how the EU smiled while Spanish banks cooked the books strongly suggests that there has been little or no pressure from the EU to pass funds from the European Social Fund onto lenders (in spite of Senor de Guindo’s good intentions).

But perhaps the most compelling clue about the true destiny of those European funds is revealed by the announcement this week from Spanish news agency EFE.

Banco Sabadell earned between January and September this year a net profit of 265.2 million euros, 42.5% more than in the same period of 2013

Banco Sabadell is my bank and where my search began over twelve months ago. My family is stuck. We are anxious about the security of our ten percent deposit and as temporary residents we are not properly integrating with our local community. And now there is another family stuck behind us, waiting to move into the property that we should have vacated months ago.

Anyway, here’s that joke.

Q. At the end of the Spanish crisis who will own the bigger villa, the Estate Agent or the Bank Manager?

A. Neither, they both end up in la prisión.

Heh.